Original silver print photographies and projections of “Music for the Eye”

“I think that one of the roles of the artist… is to help others to rediscover their gaze (on the world and on things) and with the gaze the sense of wonder that is so fundamental according to Heschel.” 1

Let’s follow Étienne Bertrand Weill’s reasoning: what could be greater than to perceive the world and things, fully, and to be amazed by what we see? The enchantment engendered by the photographs called Metaforms by É.B. Weill is perhaps magical in nature, or in any case, “supernatural”, as Jean Arp said in a poem dedicated to his friend in 1963.2 Photographs that are magical in nature, but also, at the same time, scientific, which for É.B. Weill does not represent a contradiction in that “science has come to take over from magic in order to apprehend the world of tomorrow”.3 Understanding the world of tomorrow, that is a programme.

Except that nothing is programmed in É.B. Weill. Everything seems to start from an impulse, a movement, something fertilizing, generating the other. With an empirical sensibility, he began around 1956 by tinkering with small mobiles (graceful like Alexander Calder’s sculptures) made of wire or other sober materials, which he illuminated and subjected to simple or complex movements by exposing them in front of an open photographic chamber in long exposure. By experimenting in this way, he creates an art of the trace.

É.B. Weill imagines an art where the film would “no longer have the time to capture the contours of the object. Of the form of the object, only a new, fleeting appearance remains”. 4 He called this fleeting appearance metaform… Sometimes spectral, as in Orpheus (1959), often masterful, as in Magnificat (1963), it is always spiritual.

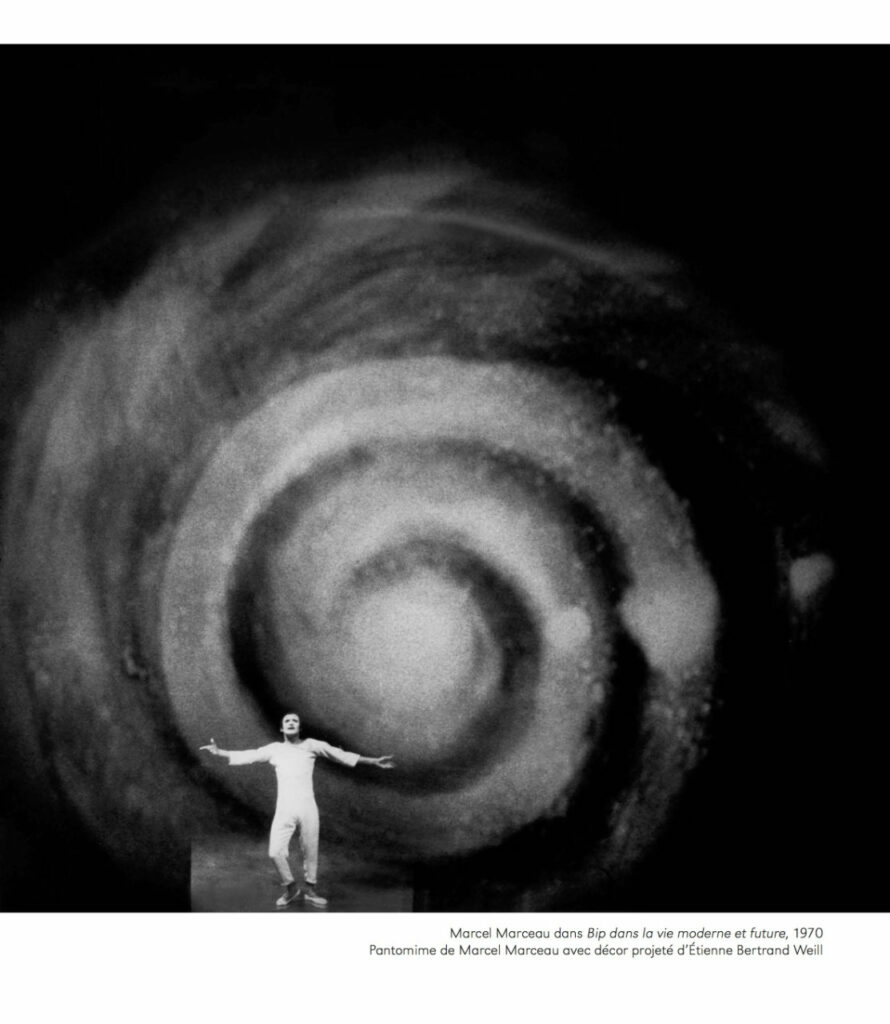

The search for a poetic and spiritual art that suggests more than it defines, that erases matter or disturbs perception to make visible the spirit of things, their trace, their invisible and hidden force, reminds me of Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetics. É.B. Weill’s meta-form is also an absence of meaning that signifies more: “When a movement is begun, it no longer has any meaning, it only has meaning at the beginning and at the end”. 5 It is in this “momentary suspension” of meaning that É.B. Weill’s art can originate. The meta-form is the form in gestation. It is a work in dialogue with other artistic disciplines. Like Mallarmé’s verse, É.B. Weill’s pictorial art sounds like music. It also breathes theatre (Jean-Louis Barrault), mime (Marcel Marceau, Étienne Decroux), painting (Jean Arp), poetry, dance and architecture. A humanist, É.B. Weill has worked with all these art forms, and the spirit of total art characterises all his work.

Music is omnipresent in the Metaforms. His research is not far removed from that of Vassily Kandinsky. In 1946, É.B. Weill created the work Recherches pour évocation musicale: figure en fil de fer, flûte, ondine, which precedes Metaform works such as Kinor (1960), Musiques pour Cordes (1965) or Jeux d’Orgues (1964). Like V. Kandinsky, he continued the correspondence between music and pictorial art (Farben und Klänge). Only, instead of canvas and pigments, he composes with light and movement, with the immaterial.

Thus É.B. Weill invented a new type of kinetic photography born of the encounter between sound and light, matter and movement. Photographs whose architecture is similar to that of music: “Like music, the Metaforms are created by the distribution in time and space (volume) of various vibrations or modulations. When an object moves during a given time, it generates a modulation perceptible to the eye through the camera. As this modulation becomes an object, the succession of various modulations thus created, through their sequence, their metamorphoses, their oppositions, their fugues, their breaks, their rhythms, etc., become elements of visual music”. 6

From there, it is only a short step to the fading of the material world. This can be sensed in his audiovisual projections Musiques pour les yeux from the 1970s, which are so far ahead of their time, replacing traditional theatrical stage design. “It is the explosion of the set, the formula of the future”, in his own words. We also see this in the broken columns in Proposition de décor classique (1963) and Hommage à Piranèse (1964). In É.B. Weill’s art we are touching on the aesthetics of the sublime. Far from static beauty, we are at the heart of moving movement, imbalance, expansion, explosion and life. Or as J. Arp would say… an astral combing… ropes of stars… photographers’ hurricanes… vibrations and waves of flowers. 7 If illustrious predecessors (Étienne-Jules Marey, Eadweard Muybridge, Norman McLaren) before him were interested in movement, É.B. Weill, through his interdisciplinary dialogues with music, theatre, mime and dance, created an art form with a truly lyrical, spiritual and experimental vocabulary.

Maria Wettergren

mariawettergren.com